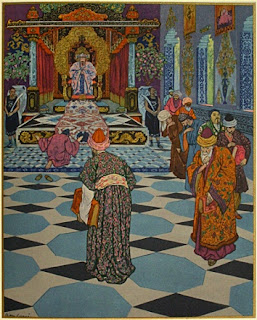

Illustration by Leon Carre from 1001 Arabian Nights

This post follows on from the previous Abbasid themed post Under the Black Banner which charted the rise to power of the Abbasid dynasty and the reign of Mansur, the founder of Baghdad. Following Mansur's death whilst on pilgrimage, his son Mahdi was confirmed on the spot as the new caliph.

Mahdi was a more chilled out character than his formidable father Mansur. He liked girls, poetry and the occasional glass of wine with meals. This did not make him dissolute, however. Rather he was perhaps more well rounded in his outlook and had been well prepared for rule by governing the east on his father’s behalf from the city of Rayy. Certainly his initial approach towards his subjects was conciliatory, having made the grisly discovery of the remains of dozens of members of the Alid family, men women and children, murdered by his father and hidden in a store room in Baghdad; each with a label attached to their ear identifying them. Mahdi had the remains buried in secret in a mass grave and the site promptly built over. He then reached out to the surviving Alids, pardoning some of those who had joined the rebellion of the Pure Soul and even appointed one of their sympathisers as his vizier. He then embarked on a programme of restoration of mosques throughout the caliphate, in the process stripping away much ostentation added in the pomp of the Umayyad dynasty and returning the interior of buildings to their original simplicity. In 777 he set out on the pilgrimage to Mecca with the intention of winning hearts and minds in the old country, dispensing much largesse and restoring the Kaaba. Accompanying him on this important expedition and making his first appearance on the public stage was Mahdi’s son Harun, imagined below as a young man. Mahdi had many sons by wives and concubines but only two mattered and these were the sons of the former slave girl Khayzuran, who he had freed and married on his accession. She was a legendary beauty who had the caliph wrapped around her delicate finger. Harun and his elder brother Musa were groomed from the beginning to succeed their father in turn. Harun appears to have been especially favoured and there is no doubt that he was his mother’s golden boy. For whatever reason, Khayzuran and her older son Musa were never close and instead she used her considerable influence on behalf of Harun. As tutor to his second son Mahdi appointed his best friend Yahya the Barmakid who cultivated a network of support around his young pupil as factions began to develop in the Abbasid court.

In 780 Harun accompanied his father on a military expedition as

Mahdi set out to show himself not just a pious leader of the Muslims but a

warlike one as well, committed to the pursuit of jihad against the infidel. The

Byzantine commander Michael Lachanodrakon had led a

successful invasion of northern Syria two years before, capturing the

settlement of Marash whilst the Arab response had achieved nothing of note. Leaving

Musa in charge in Baghdad, Mahdi escorted Harun to the frontier and then sent

him off at the head of a small raiding

force to win his spurs. The raid was a moderate success. A small fortified

settlement was captured and plundered and the troops were back across the

frontier before any serious opposition could be marshalled by the Byzantines.

Meanwhile a larger force was sent further into imperial territory where it

suffered a significant defeat at the hands of Lachanodrakon.

In 780 Harun accompanied his father on a military expedition as

Mahdi set out to show himself not just a pious leader of the Muslims but a

warlike one as well, committed to the pursuit of jihad against the infidel. The

Byzantine commander Michael Lachanodrakon had led a

successful invasion of northern Syria two years before, capturing the

settlement of Marash whilst the Arab response had achieved nothing of note. Leaving

Musa in charge in Baghdad, Mahdi escorted Harun to the frontier and then sent

him off at the head of a small raiding

force to win his spurs. The raid was a moderate success. A small fortified

settlement was captured and plundered and the troops were back across the

frontier before any serious opposition could be marshalled by the Byzantines.

Meanwhile a larger force was sent further into imperial territory where it

suffered a significant defeat at the hands of Lachanodrakon.

Two years later Mahdi launched a much larger

expedition intended to reassert the dominance of the caliphate. His timing was

good, the empress Irene, pictured below, was in the midst of purging her forces of iconoclasts

and the Arab forces could hope to take advantage of the dearth of leadership

amongst the Byzantines. Over ninety thousand men were sent across the border

under the overall command of Harun, accompanied by his father’s trusted

ministers Rabi ibn Yunus and Yahya the Barmakid. Rather than confining his

activities to the border regions, Harun pushed westwards into the Byzantine

heartland, whilst Yahya took a portion of the army northward and inflicted a

defeat upon Lachanodrakon. Harun’s army won another victory near Nicaea and

then he advanced all the way to the shores of the Bosporus, from where he could

look across the straits to the capital of the infidel. That however was as far

as he could go and without a fleet to carry him across to Constantinople, his

advance to the sea was largely symbolic. After much plundering Harun turned for

home but now found that Rabi, who had been left to guard his lines of supply

had been defeated and driven back. The young Abbasid prince now found himself

trapped between two Byzantine armies close to Nicaea. The most famous caliph of

them all could have been reduced to an obscure footnote right then and there

but his luck was in. The Armenian commander Tatzates had reason to fear that he

would soon become another victim of Irene’s purges and so he took the

opportunity to defect, taking many of his troops with him. The Byzantines now

decided to negotiate and Irene’s chief minister Stauracios ventured into the

enemy camp at the head of a delegation. Harun, having given no promise of safe

conduct and advised by Tatzates of the empress’ reliance on the eunuch, took

the envoys prisoner. Desperate to secure the release of her favourite, Irene

agreed a humiliating three year truce with the caliphate, allowing Harun to

withdraw triumphantly, having secured an annual tribute of seventy thousand

gold pieces and ten thousand pieces of silk.

Back in Baghdad the court poets praised Harun’s

achievement to the skies, declaring that he had advanced to the walls of

Constantinople itself and placed his spear against them before sparing the city

in return for tribute. He was given the epithet of al Rashid – the right guided.

Oaths were taken to him as the heir to his elder brother. The favoured son had

done well but yet he was not the first in line. It may have been that Mahdi had

decided to elevate his second son to first place when he set out along with

Harun in 785 to visit his eldest son Musa at Gurgan beside the Caspian, where

he was busy putting down a rebellion. On the way however, so one story goes,

the caliph set out hunting and pursued a gazelle amongst some ruins. As his

horse galloped below a lintel, the caliph, absorbed by the chase, forgot to

duck and that was the end of Mahdi who was laid to rest beneath a nearby walnut

tree. An alternative version has the caliph accidentally poisoned by one of his

concubines who had sent a poisoned pear to a rival. Mahdi, taking a fancy to

the fateful pear, intercepted it on its way and ate it. Take your pick, Dear

Reader, either way the end result was the same.

At this point Harun played the part of the faithful

brother, sending his father’s signet ring to Musa whilst returning to Baghdad

to restore order. The troops in the city who had rioted at news of the caliph’s

death were quieted with a large payment from the treasury and Harun took oaths

of loyalty from the great and the good in his brother’s name. As always Rabi

and Yahya were at the heart of events, pulling strings and greasing wheels. Taking the name of Hadi, the

new caliph marched back from the east in just twenty days to take control in

Baghdad. Hadi was tough and aggressive, the darling of the military, whilst the

more cultured Harun enjoyed the support of the court bureaucracy and he was of

course his mother’s favourite. Khayzuran now wielded considerable power as the

widow of Mahdi and the mother of Hadi and Harun. At her sumptuous palace on the

east bank of the Tigris she received suppliants each day, begging for favours

and appointments and soon it seemed that all the business of the state was in

the hands of the former slave girl, much to the annoyance of the caliph.

Finally Hadi issued a threat that anyone approaching his mother looking for

advancement would lose his head instead. Anyone doubting his word had only to

glance at the permanently drawn swords of his bodyguard to know that he meant

business. Hadi, set out to further marginalise his mother and brother by

seeking to alter the plan of succession in favour of his own son Jaffar, who was the preferred

choice of many of the army commanders, disinheriting Harun. Hadi was advised

against this action by Yahya the Barmakid who pointed out that if the sacred oaths

taken to Harun were disregarded, then no oath would ever have the same binding

effect again. This argument gave the caliph pause for a time but then he lost

his patience and decided to act. Having successfully poisoned the vizier Rabi, who

was a key ally of Khayzuran, he then tried to do the same to his mother.

Khayzuran took the precaution of feeding the dish of rice he sent her to her

dog. Finally Hadi declared that Jaffar would succeed him and demanded oaths

of allegiance to be taken to his son. He

then had Harun and Yahya the Barmakid arrested when they attempted to flee the

court. At his moment of triumph however, the caliph fell foul of his mother who

returned his compliment with greater subtlety, using her contacts amongst the

caliph’s harem to have him poisoned and then suffocated with pillows as he lay

ailing. He had reigned for just over a year. Khayzuran now used her own

contacts in the military to secure Harun’s succession. Jaffar was dragged from

his bed at sword point and forced to renounce his claim to the caliphate and

Harun was duly installed as the new Commander of the Faithful without further

opposition.

There now dawned a golden age, so posterity would have us believe.

Peace descended upon the Muslim world and Harun ruled wisely in sumptuous

splendour and refinement, surrounded by poets and scholars. His reign is

perceived, through the rose tinted distortion of later generations’ nostalgia,

as the highpoint of Arab cultural and intellectual achievement. There is

however a darker tale to be told which reveals Harun to be far from the

Solomon-like right-guided ruler of legend. Strip away the romance of the

Thousand and One Nights and we are left with an insecure, jealous, vicious and

naive ruler.

Yahya the Barmakid was a critical influence in Harun's succession

The Abbasids had swept to power on a tide of popular support,

stirred up by their man in Khurasan Abu Muslim. Restoration of the leadership

of Islam to the family of the Prophet from the dissolute Umayyads had been their

rallying call. The masses had looked to the revolution to bring about an

improvement in their fortunes but Abbasid rule had in the end merely delivered

more of what had gone before. Mansur had fulfilled some of the early promise of

the dynasty, appearing before his people and hearing their complaints in

person, although he had ruthlessly persecuted the Alids. Mahdi too had made

some efforts at restoring the simplicity of the faith, although he had been

more pleasure-loving than his austere father. Neither had done much to better

the lot of the vast majority of their subjects however and both had faced

rebellion, seemingly forgetful of the discontent that had brought them to power

in the first place.

For the rural poor the burden of taxation was heavy and in most

places a system of tax farming left tax collection up to private enterprise,

whereby rapacious officials sought to wring as much personal profit out of the

unfortunate tax payers as they could. The result was impoverishment of the

peasant farmers, who often abandoned the land

or were deprived of their property when they could not repay the loans

they were forced to take out in order to pay their taxes, for which the whole

community was collectively responsible. The land was snapped up by the wealthy

and vast estates became the personal property of the ruling family and their

cronies. This was nothing new of course. The story is a familiar and recurring

one. Across the frontier in the Byzantine Empire the same situation existed but

the plight of these small farmers as the backbone of the military was

periodically addressed and the trend reversed. In the caliphate the peasant

farmer played no military role and the soldiers who had come west with the

conquerors from Khurasan, known as the

abna, were maintained by the state.

Far from being a period of peace, Harun’s reign saw the caliphate

plagued by rebellion from end to end. As their discontent and disillusionment

grew, the rural peasantry of the caliphate were attracted to new revolutionary

movements, which sprang up like mushrooms, all of them promising to make the

caliphate anew and deliver a fairer

future. In the east of the empire a succession of movements fused elements from

the pre-Islamic Persian past with more recent history. The old ideals of Mazdakism;

a Zoroastrian ideology akin to communism which had been ruthlessly repressed by

the Sassanid rulers of Persia, were given an Islamic make-over by associating

them with the memory of Abu Muslim, the man of the people slain by the

ungrateful Abbasids. The first leader of these movements was the so-called

veiled prophet, a former lieutenant of Abu Muslim from Merv, who claimed to be

a reincarnation of his murdered commander. He had hidden his face behind a

green silk veil either because, according to his adherents, his face was so

radiant that it could not be seen by mere mortals or, according to his enemies, he

was one-eyed, bald and ugly. Whatever the truth, through revolutionary rhetoric

and cheap conjuror’s tricks he amassed a great following and some sixty cities

in Khurasan and Transoxania joined his cause. The veiled prophet had been

finally run to ground and had taken his own life in 779 but he spawned a succession

of imitators whom the credulous peasantry were prepared to follow in the hope

of a better lot in life.

The cult of the Alids too was linked to ideals of social reform,

for Ali had been the champion of the ordinary people and had stood for the

equality of all Muslims. A rebellion raised in Medina in 786 by the Alid Yahya

ibn Abdullah had garnered only lukewarm support following the good works of

Mahdi and Khayzuran in the region. Evading capture, the rebel moved onto

Daylam; the region south of the Caspian and here succeeded in sparking a

widespread popular revolt. He was finally persuaded to give himself up in 792 whereupon

he was promptly murdered.

In many places across the

caliphate, those perennial malcontents the Kharijites were resurgent, rejecting

the authority of the caliph and condemning the luxury of his court. A Kharijite

led rebellion began in northern Iraq shortly after Harun’s accession and then the

rebels marched north into Azerbaijan and overran the province for a period of

two years before they were finally put down. In Egypt there were repeated

uprisings beginning in 789 in protest at the increases in land taxes. The

rebels were crushed by pouring troops into the region before the taxes were

increased again, sparking further revolt. When Harun decided to cut the pay of

the troops stationed in Egypt they joined in with the rebels and burned the

city of Fustat to the ground.

In the administration of his empire Harun continued to rely

primarily on the Barmakids. His old tutor Yahya would serve as Harun’s vizier

whilst Yahya’s two sons Fadl and Jaffar, who was the caliph’s closest friend

and favourite companion, held a succession of important offices of state and

were trusted with the governorship of large territories. Fadl in particular

would prove to be a capable administrator during his time as governor of

Khurasan; quelling rebellion, ploughing funds into improving infrastructure,

curbing the worst excesses of the tax collectors and winning hearts and minds,

whilst keeping up the flow of funds to the treasury. The primary interest of

the Barmakids however remained the feathering of their own nests and the strengthening

of their own network of support.

Illustration by Leon Carre from 1001 Arabian Nights

For many

years Harun was content to let them get on with it. He kept up the conspicuous

acts of piety expected of a caliph by dispatching the yearly raids, known as razias, across the frontier into

Byzantine territory and undertaking the hajj on no less than eight occasions

during his reign. Harun remained however, for the overwhelming majority of the

time, in glorious isolation and devoted to pleasure. The caliph, his wives and

concubines, his mother and relatives, his administrators and courtiers and hangers-on

lived in a world of opulent palaces, exquisite gardens and massive excess. The

quantities of wealth that were thrown around were obscene. Harun’s favourite

wife Zubayda ate from golden plates, wore so many jewels that she could not

walk unaided and had a staff of twenty simply to care for her pet monkey. She

rewarded flatterers by filling their mouths with pearls. His mother Khayzuran had

a reputation for pious works, financing shrines and way-stations along the

pilgrimage route to Mecca. As such she was popular. Her personal wealth was

immense however. As one of the greatest landowners in the caliphate she spent

vast sums on land improvement and irrigation, although primarily for her own

benefit and half of the land tax revenue of the caliphate is rumoured to have

flowed straight into her coffers. When in a more frivolous mood, Khayzuran

could spend up to fifty thousand dinars on a single piece of material and is

said to have owned eighteen thousand dresses at the time of her death in 789.

Such excess was not the preserve of the court women. Harun once rewarded an

amusing poem by his feckless brother Ibrahim with a gift of a million dirhams

from the treasury and showered his coterie of nadim; intelligent, cultured and witty drinking companions with

palaces, wealth and status. Outside of the royal family the Barmakids enjoyed

almost comparable wealth and practiced similar largesse.

Despite inhabiting a world of palaces and gardens, Harun nevertheless tired of Baghdad. He disliked the heat and the proximity of the bustling masses and in 796 he established a new capital at Raqqa to the north. Here he could withdraw, accompanied by his household and his favourites and spend his days playing polo, hunting and practicing archery and his evenings in the convivial companionship of his nadim, enjoying poetry, discussion and chess. Raqqa was also closer to the frontier and Harun was once more taking a serious interest in war against the Byzantines. In 797 he sought to reprise the glorious campaign of his youth and once more crossed the frontier in person. He had chosen his moment perfectly for the empire was in a state of unrest. The empress Irene had just blinded and killed her son Constantine and her grip on power was tenuous whilst the loyalty of her armies was uncertain. The Byzantine response to Harun’s invasion was muted in the extreme and the caliph’s forces once more spread out into enemy territory with one column penetrating as far as Ephesus on the Aegean coast. Panicked, Irene sued for peace once more, agreeing to similarly humiliating terms as she had in 782 and Harun’s triumphant forces marched home unmolested, laden down with plunder.

The embassy of Charlemagne to Harun al Rashid

Back in

Raqqa, Harun now received an embassy from Charles, king of the Franks. Charles

had little to offer Harun, who as the richest and most powerful ruler in the

world vastly outstripped him in wealth and territory. If Charles already

harboured pretentions towards the imperial crown of the west however, then

establishing good relations with the greatest enemy of the eastern Roman Empire

was a sound strategic move in the event of hostilities with Byzantium. For his

part Harun welcomed a potential ally who could harass his sworn foes but was

too far away to pose any threat to himself. Having given certain assurances

concerning the safety of pilgrims visiting the Christian holy places in his

territory, the caliph sent the envoys on their way laden down with gifts and

accompanied by an elephant. The elephant, named Abul Abbas, made his way

through north Africa and Italy, accompanied by the only member of the

delegation to survive the return journey, arriving in Charles’ capital Aachen

in 802. He lived for another eight years as a major celebrity at the Frankish

court.

Harun appeared to be a man in control. He had overcome numerous rebels and malcontents, he had humiliated the empress and vast amounts of wealth were pouring into his treasury. But was he really in charge? It was time to make some very big decisions and show everyone who was boss.

Part 2 Here

http://slingsandarrowsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2015/09/harun-al-rashid-part-two-fall-of.html