It was the

greatest city in the world and its people knew it.

From its founding

by Constantine the Great in 330 AD as a new Rome in the East, through the monumental

military efforts in the reign of the emperor Justinian in the Sixth Century to

recover the Western Empire, to the desperate struggle of the fighting emperor

Heraclius to hold back the tide of the Arab conquests, the rulers of

Constantinople had unfailingly seen themselves as the inheritors and

continuators of the Roman Empire. They had striven continually to assert their

God-given right to rule as the pre-eminent sovereigns on earth even as their

once great empire shrank and crumbled.

16th Century icon depicting the final siege of Constantinople

Constantinople

nevertheless remained a city of marvels, a bastion of Christianity and a time

capsule of a lost Roman civilisation which inspired wonder and envy in all

those visitors who beheld it. Defiantly it had stood firm against the

burgeoning Steppe nations pressing southwards from beyond the Danube frontier: Huns,

Avars and Slavs had been turned back in despair by the mighty Theodosian Walls

that protected the city on its landward side. The forces of the Umayyad Caliphs

had been vanquished by the terror weapon of Greek fire and their great invasion

fleets had burned in the waters of the Bosporus as they had sought to assail

the city from the sea.

It

was to its superb location and defences that Constantinople arguably owed its

survival into the Eighth Century AD. Constructed on the site of the ancient Greek city of Byzantium,

Constantine’s new Rome occupied a horn-shaped promontory jutting out from the

western shore of the Bosphorus. Protected on one side by the waters of the

Propontis and on the other by the great natural harbour of the Golden Horn, the

city presented an insurmountable challenge to any would-be besieger.

Approaching

from the west, the visitor to imperial Constantinople would be

immediately struck by the scale of the walls. Originally constructed in the

Fifth Century under the auspices of the somewhat feeble Eastern Roman Emperor

Theodosius II, the land walls of Constantinople would stand un-breached for a

millennium. Not until the advent of gunpowder would they fail the city. Even

the terrible Attila had turned away in despair at the sight of the walls that

protected the capital of the Roman East.

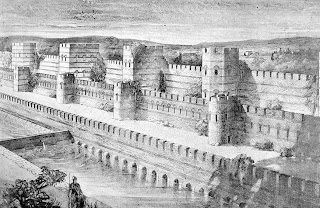

The Theodosian Walls

The

walls stretched for four miles across the neck of the peninsula from shore to

shore, anchored by the massive defences of the Blachernae Palace beside the

Golden Horn and meeting the sea walls at the formidable Tower on the Propontis.

From these two points the Sea Walls surrounded the rest of the city. The land

walls comprised three lines of defence. A moat sixty feet wide divided by a

series of dams to maintain the water level across the undulating landscape was

the first obstacle facing any would be attacker. Beyond this the outer wall

rose thirty feet high and featured no less than 96 towers. Sixty feet behind

the outer wall rose a second higher wall, forty feet in height and bristling

with another 96 larger towers which were positioned in between the outer towers

so as to provide a clear field of fire for the artillery stationed atop them.

They were the last word in defensive engineering.

Five

principle gates led through the walls. On great occasions of state the

southernmost of these was the gate of choice for making a grand entrance. The

Golden Gate was constructed from white marble. Like the other gates of the city

it was flanked by massive square defensive towers which were topped off by

figures of winged Victory. Its ornate doors were covered with golden bosses and

atop the gate was an ostentatious monumental quadriga drawn by elephants.

Passing

through the Golden Gate the visitor would proceed along the main thoroughfare

of Constantinople known as the Mese.

This long colonnaded street led eastwards through the heart of the city towards

the eastern tip of the peninsula, occasionally opening out into increasingly

grand public spaces with triumphal columns rising up out of their centres and

plundered sculpture from throughout the ancient world gracing the plinths

around which the populace would mooch and mingle. Running parallel to the Mese,

the Aqueduct of Valens brought fresh water into the city on bounding arches,

remaining in use well into Ottoman times. At the end of the Mese stood the Milion. This was a golden milestone displaying distances to all the

great cities of the empire. It stood within an elegant tetrapylon; a square structure consisting of four arches topped by

a vaulted roof. Beyond the Milion was

the public square of the Augustaion,

where a seventy metre high column sheathed in bronze rose above the city. It

was surmounted by a great equestrian statue of the emperor Justinian, holding a

globe in his hand and wearing a crown of peacock feathers.

North of

the Augustaion stood Justinian’s

finest construction and greatest legacy, the church of Hagia Sofia. Built upon

the smoking ruins of its predecessor, burned down in the destructive riots

unleashed by the Constantinopolitan mob in 532, the new Hagia Sofia was

intended as a signature project of unparalleled magnificence. Justinian sourced

his building materials from throughout the empire. Marbles of different hues

were brought from Egypt, Syria and Greece and the most talented architects,

craftsmen and mosaicists of the day were employed to create the most sumptuous

interior possible, calculated to inspire awe in all who beheld it. The Emperor

himself upon seeing the finished interior with typical modesty uttered the

words ‘Solomon I have surpassed thee!’

The Hagia Sofia pushed the envelope not only

aesthetically but also architecturally by being the first structure to employ

pendentives; inverted triangular sections of masonry which solved the problem

of placing a circular dome on top of a square building, allowing the weight of

the dome to be translated downward to the supporting piers at each corner and

providing a far more elegant solution which would spawn many imitators but few

equals. It remains one of the world’s great buildings.

Retracing their steps from the Augustaion back onto the street the

visitor could continue eastwards, with plumes of steam rising from the Baths of

Zeuxippos to their right, towards the great gate of the Chalke which led through into the grounds of the imperial palace. Looking

to their north-east they would see the top of the great red brick basilica

topped by a rotunda known as the Magnaura which served as a senate house and

imperial audience hall. Passing through the Chalke, if they were sufficiently

privileged, the visitor would perhaps glance up to see a great painted icon of

Christ which looked down from above the archway. As the iconoclastic controversy

had raged in the Eighth and Ninth Centuries the icon had been taken down,

replaced, destroyed and finally remade.

Beyond the Chalke

were the barracks of the elite regiments of Imperial guards; the Scholae and the Excubitors, literally; ‘those who do not sleep’ charged with the

emperor’s protection, their commissions purchased at great expense by their

families. Heading southwards towards the palace, a series of halls and

courtyards provided spaces in which the great and the good could gather to await

the emperor’s pleasure. Most noteworthy was the Triklinos of the Nineteen Couches. This was an oblong hall with nine apses

along each side which was used for

ceremonial banquets. It featured, as the name suggests, nineteen ornate dining

couches.

Passing through the hall the visitor then

reached the palace complex of Daphne. This was the original imperial residence

constructed in the time of Constantine. Here the imperial apartments were arranged around a central courtyard. They were reached by passing through the octagon, a domed chamber in which the emperor would be clothed in his imperial vestments before embarking on any official business. In the grounds

of the palace stood the chapel of St Stephen, which was built to house the

relic of that first Christian martyr’s right arm.

The imperial palace complex grew over the

centuries as successive dynasties added to the site, constructing newer and

grander buildings on a series of terraces that led down to the sea. Justinian’s

successor, his nephew Justin II, created a new throne room known as the Chrysotriklinos. This domed, octagonal

structure leant itself to the pageantry of the Byzantine court. Its shaped

allowed for a series of chambers to be curtained off from public view, allowing

members of the imperial family and other notaries to make an entrance from all

points of the compass. In the eastern apse a throne was positioned beneath a

mosaic of Christ.

By the Ninth Century the older parts of the

palace were becoming run down and fell out of regular use. The emperor

Theophilus created a new palace down by the sea called the Boukoleon, built into

the sea walls and served by its own private harbour. Theophilus loved pomp and

ostentation more than most Byzantine emperors and was most concerned with

outdoing his opposite number the Abbasid Caliph. Throughout the palace splendid

decor was the order of the day. Although the imperial family no longer lived in

the old palace, its buildings remained in use for occasions of state, providing

an important symbol of continuity with the past. Following reports from a

delegation to the Abbasid court, describing the automata in the Caliph’s throne

room, Theophilus commissioned his own. They included a golden organ which

played to itself and was set up in the Chrysotriklinos and a golden plane tree

filled with gilded bronze and silver birds which moved and ‘sang.’ The golden

tree was set up beside the so called ‘Throne of Solomon’ in the Magnaura upon

which more birds were arraigned. Here foreign delegations were received. A

concealed lifting mechanism allowed the throne to be lifted into the air, so

that the emperor looked down from on high upon any suppliants who came before

him. It was guarded by a pair of gilded lions who moved and ‘roared’ at the

emperor’s command. The emperor’s toys were melted down by his good for nothing

successor Michael III ‘the sot’ in his endless search of gold to squander on

idle pleasures, but they were not forgotten and by the reign of Constantine VII

in the Tenth Century replacements had been crafted. Constantine too had a great

love of imperial pageantry. His principle contribution to posterity is his De

Ceremoniis; a painstaking blow by blow account of Byzantine court ceremonial,

as dull as it is informative.

The existence of the automata are attested by

the western diplomat Liutprand of Cremona who visited Constantinople twice on

official missions for the Italian ruler Berengar II and the Holy Roman Emperor

Otto I. In his memoirs Luitprand, at pains to stress that he was unimpressed by

these geegaws, writes:

In front of the emperor’s throne was set up a tree of gilded bronze, its branches filled with birds, likewise made of bronze gilded over, and these emitted cries appropriate to their species. Now the emperor’s throne was made in such a cunning manner that at one moment it was down on the ground, while at another it rose higher and was to be seen up in the air. This throne was of immense size and was, as it were, guarded by lions, made either of bronze or wood covered with gold, which struck the ground with their tails and roared with open mouth and quivering tongue.

The ruins of the Hippodrome

When Constantinople fell to the forces of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 the city was systematically looted. The ancient monuments of the hippodrome were stolen or melted down, most famously the four horses from above the carceres which were taken away to Venice. The palace complex was ransacked and Hagia Sofia was desecrated with horses brought into the building to assist in the carrying away of plunder and a drunken prostitute enthroned on the Patriarchal seat. When the Byzantine Emperors returned sixty years later they left the imperial palace in its abandoned state and set themselves up in the palace of Blachernae in the north-western corner of the city. The city would remain a shadow of its former self until its final capture by the Turks in 1454. With the notable exception of the Hagia Sofia, only crumbled vestiges now remain of what was once the Queen of Cities.

19th Century view of the Theodosian Walls

More from Liutprand of Cremona

More on the walls

More on the palace

Constantinople comes to life with Byzantium 1200

More Byzantine History from Slings and Arrows